How to Interpret the Inventory Age Metric

By Dan Zeiger, Institute of Supply Management

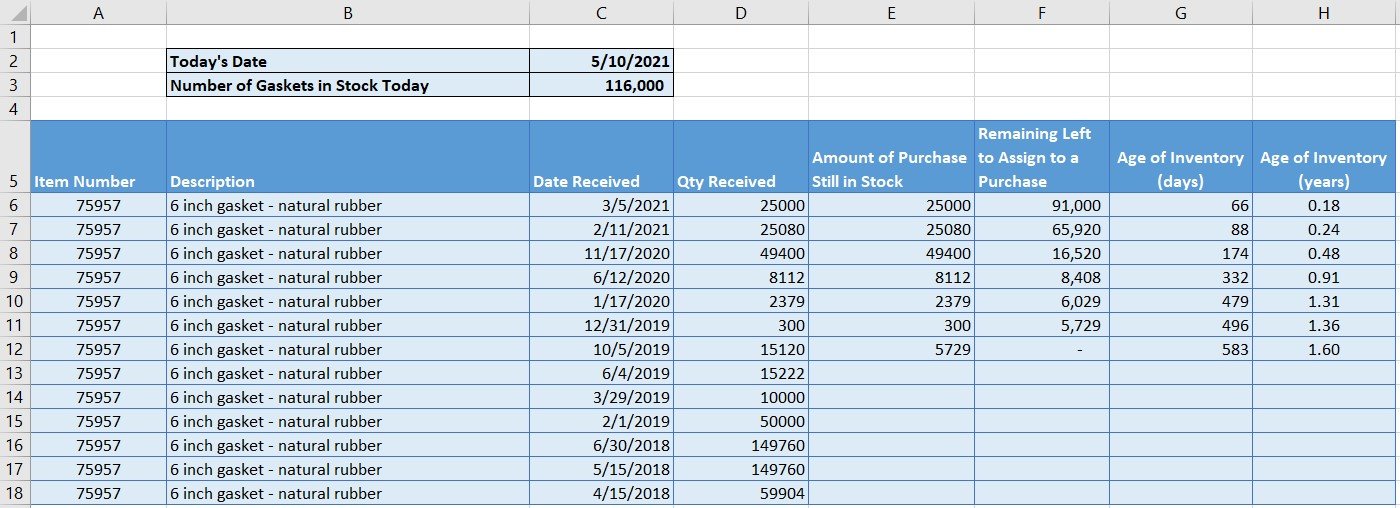

How to calculate inventory age.

The delayed deliveries, product shortages and empty shelves that typified the height of the coronavirus pandemic challenged the just-in-time (JIT) model, causing many companies to carry excess inventory.

Such heightened stock levels can be a buffer against often-volatile consumer demand and unexpected supply disruptions — as well as the next global crisis. However, that strategy is not without its own risks: Carrying excess inventory comes at a cost, especially when it doesn’t sell, and becomes more of a risk as it lingers.

COVID-19 resulted in many organizations over-ordering to protect against stockouts, says Tracey Smith, MBA, MAS, CPSM, president of Numerical Insights LLC, a boutique analytics firm in Williamsville, New York. “That can lead to inventory sitting on the shelf longer and becoming ‘older,’ ” she adds.

Inventory management is a constant tightrope. Companies and practitioners must ensure supply while limiting the cash tied up in inventory. Finished goods that don’t sell or aren’t used quickly or parts that aren’t readily used in production take up space and require more employee time to address. And should those items become dead (or obsolete) inventory, they represent a lost opportunity for revenue and profit.

For a company that carries debt, Smith points out, a bank review often includes an assessment of the percentage of inventory more than a year old. Such financial implications and impacts make this month’s metric, inventory age, so critical.

Even for items that are inexpensive and/or have long shelf lives, Smith says, inventory age is important to track, particularly in tandem with inventory turnover ratio.

“There are many risks involved in keeping inventory for a longer period of time,” she says. “Part numbers can be superseded, making those you have obsolete. A finished good can reach the end of its life cycle, and the company may decide to stop producing it, so all materials associated with that product will become obsolete unless they can be used in other parts.”

When a product or part gets up in age with fewer turns, she adds, a company should conduct a deep analysis of its inventory to determine why items are sitting. It must also consider options for aging products and parts in stock before they are classified as scrap.

Meaning of the Metric

Whether an organization relies on a manual or automated process to determine inventory age, a first-in, first-out (FIFO) system is the most common basis, Smith says. She recommends client companies track the percentages of inventory in stock for:

Less than 90 days

Ninety to 180 days

Six months to a year

More than a year.

Inventory turnover ratio is an ideal companion metric because it can help find “hidden” stock-keeping units (SKUs) that are obsolete or in danger of becoming so, Smith says. “A company that operates with hundreds of SKUs can easily have an old bill of materials in its ERP system that is still active and long forgotten,” she says. “If a raw material SKU doesn’t turn, it’s either a hidden obsolete part and needs to be dealt with, or it’s being prepared for a new finished product.”

While as with most inventory metrics where every SKU is different, four inventory turns a year is an ideal goal, Smith says, meaning an item should ideally age no more than three months. She generally considers products or parts on a shelf for more than a year to be dead inventory.

Although many of her client companies haven’t been significantly impacted by lower demand, Smith has advised judicious buying and paring down of aging inventory. Larger safety stocks are typically restricted to items with longer lead times; for example, while China has relaxed its zero-COVID policy, production shortages have continued, so some clients have found alternate suppliers in the U.S.

“It’s a two-supplier strategy — one with longer lead times and lower cost and another with short lead times and higher costs,” she says. “The two are blended to meet production needs if (the company) is will to pay slightly more to avoid delays.”

During the pandemic, one of the highest-profile examples of inventory age has been in health care, involving products already produced and sold: personal protective equipment (PPE) and other medical supplies.

With a limited shelf life for PPE, hospitals’ financial risk is no less worrisome. However, even as facilities scrambled to find supply as the pandemic raged, some health-care trade associations warned against proposed stockpile-requirement legislation. Even as COVID-19 cases have receded in severity, hospitals have been diligent to use up their PPE inventories.

“The issue for hospitals: Is stockpiling sustainable?” Nancy LeMaster, MBA, Chair of the Institute for Supply Management® Hospital Business Survey Committee, told Inside Supply Management® in 2020. “I believe cost pressures will ultimately counterbalance the push to carry large cushions of inventory. Also, the issue of expired materials and waste will be magnified with those stockpiles.”

Case Study

One of Smith’s clients exemplifies that inventory-age risk is not always related to demand. The manufacturer produces more than 200 finished goods for the beauty industry, with each requiring its own label. When a label supplier offered volume discounts, the company’s procurement staff ordered “a warehouse full of labels,” Smith says.

The company sells products in Europe, home in recent years to many regulatory changes involving product ingredients and label-information disclosure. Such new regulations have required frequent changes to the company’s labels — making hundreds of thousands of them obsolete, even if they weren’t “that old.”

The solution belied the pandemic-fueled sentiment on inventory strategy, as it was JIT-centric. “After studying lead times, the company accepted a recommendation to order labels only after a product order is sent to production,” Smith says. “With the typical lead time of 10 weeks for production and four weeks for labels, the labels arrive in plenty of time for the production run.”

A company with at-risk inventory that it is unable to sell generally has two options: (1) returning some of the product to the supplier if the contract allows or (2) donating it to charity. “It depends on what the product or part is,” Smith says. “There may be regulations that deem it must be disposed of in a certain way.”

About the Author

Dan Zeiger is Senior Copy Editor/Writer for Inside Supply Management® magazine, covering topics, trends and issues relating to supply chain management.

Originally published in Inside Supply Management Magazine. View original post here.