How to Calculate Inventory Reorder Points and Safety Stock Values

This article provides an easy explanation of how to calculate safety stock values and reorder points for inventory management. Alternatively, you can watch the video on this page to get the same information. I’ll give you a few ways to consider safety stock and all of the formulas needed to do your own inventory calculations.

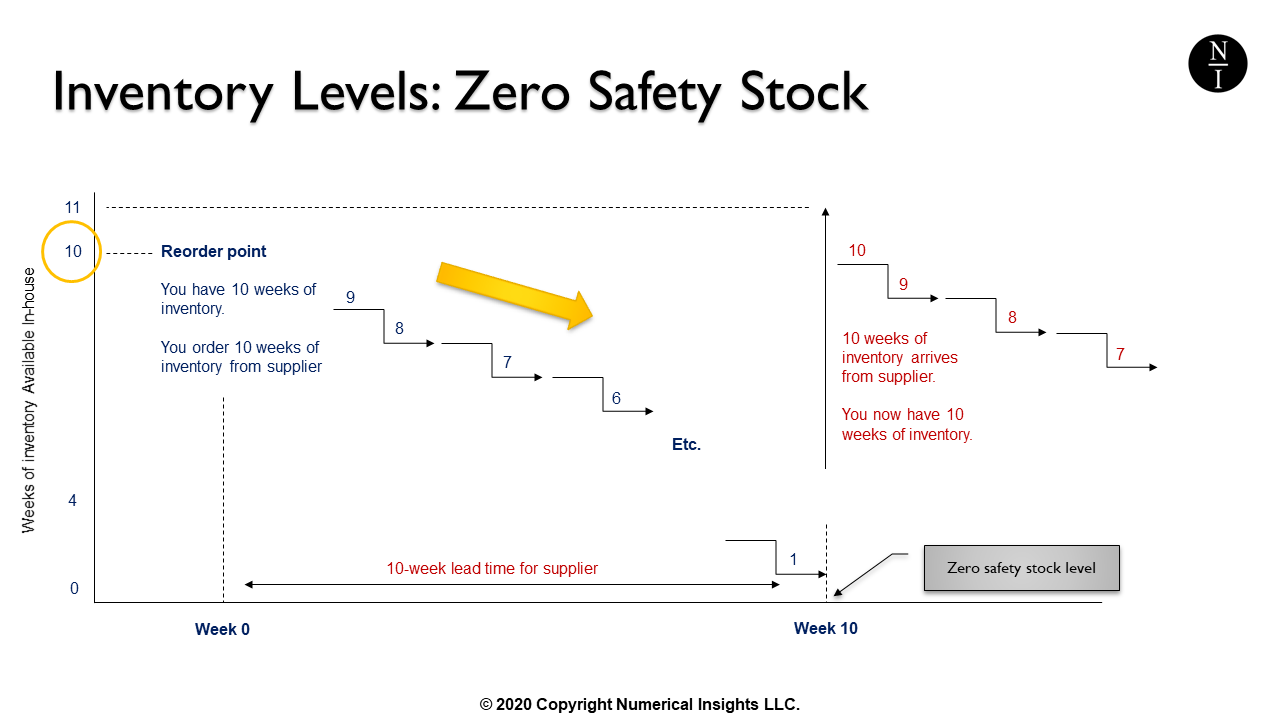

To get started, let’s look at what happens to inventory levels of just one item. This will help us understand the terms, reorder point and safety stock.

I’ll start with the scenario where we run inventory levels down to zero before new inventory arrives from our supplier. This means we have zero safety stock. Safety stock is how much inventory you want to keep as a buffer to deal with sources of variation. I’ll get into those sources of variation in a moment. For now, we’ll pretend that we use up inventory at the same rate every week so we can predict exactly when we run out.

In the scenario on the screen, this company starts with 10 weeks of inventory and as the weeks go by, the inventory is slowly depleted. If demand for this inventory is constant, then we would run out of inventory in exactly 10 weeks. Demand is never constant in the real world, but I’ll show you how to deal with that in just one second.

Since we know we will run out of inventory in 10 weeks and we see that our supplier has a 10 week lead time to get this item, that means that we must order 10 weeks of inventory when we have 10 weeks in stock. A new supply of 10 weeks worth of inventory would arrive just as we run out of the inventory we have in-house.

The Zero Safety Stock Model

The zero safety stock model is a very risky way to plan inventory since variations in demand and supplier delivery times happen every day and this makes our calculations merely estimates. All it takes is one delay in a delivery or one retailer running a promotion of your product for you to run out of inventory before the next shipment arrives from your supplier.

There’s no way to predict with 100% certainty what your inventory needs will be and very little chance that all deliveries from a supplier arrive in exactly the number of weeks or days that the supplier promises.

How to Calculate Safety Stock

Inventory planners keep safety stock to deal with this reality. Safety stock is a buffer of inventory to help deal with sources of variation. I’ve mentioned two of those sources already: variation in delivery lead times from your supplier and variations in the daily or weekly demand for this inventory item.

As a safety stock example, if I decide that I never want to have less that 1000 of this item in stock… just in case… then the safety stock level of this item is set to 1000 units.

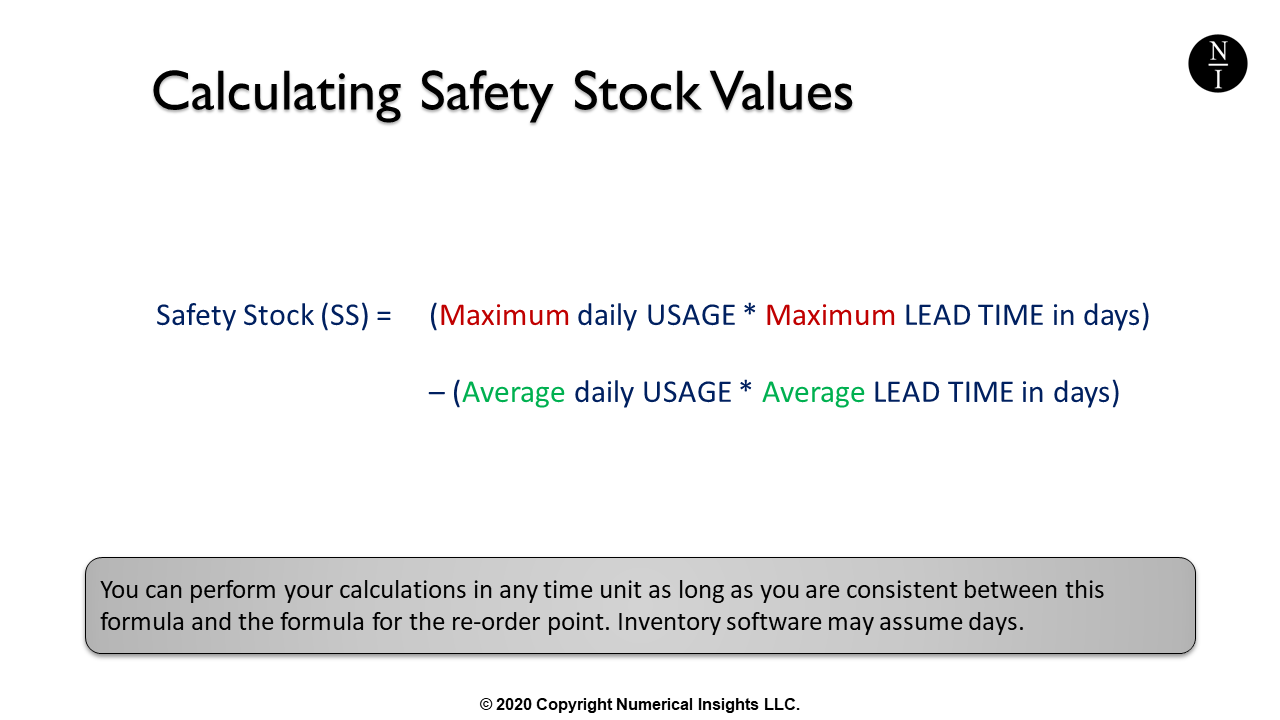

But how do inventory planners pick a safety stock level? This number was not chosen randomly. It is a function of the daily usage of this item and the variation in supplier lead times. Specifically, here’s the formula.

The safety stock equation takes into consideration what your peak daily usage was and what your average usage was. It also considers your longest lead time and your average lead time.

These are all values which can be calculated, but you need to pick a period of time over which to calculate them. For example, you may choose to do safety stock calculations once a year and use one year of historical data to calculate daily usages and lead times… or, you may choose to recalculate your safety stock levels more often. If the demand for this item has seasonal peaks throughout the year, make sure the peak time is in the timeframe you consider or you’ll under-estimate the safety stock needed and increase your risk of running out of this item in your peak season.

How often you recalculate safety stock levels is also a function of how easy it is for you to get the historical data needed. In some computer systems, these values are calculated automatically, but for many companies, trying to export historical lead times can be challenging or very manual. If it’s manual, it’s not something you wish to calculate frequently. If it’s reasonably easy to export the necessary data, then you have a greater chance of automating these calculations to make periodic recalculations a quick activity.

Sample Calculation

Let’s put some numbers in our equation to see how this works. Suppose we have a supplier that has been delivering this item to us, on average, in 14 days. However, over the last year, there have been deliveries of this item that have taken as much as 25 days to reach us.

Additionally, let’s say that we typically use about 10 of these items per day in our production line, but we also have days where we’ve used as many as 14 in a day. Putting these 4 values into the Safety Stock formula, we get a value of 210 for our safety stock level.

Next, we need to realize that we use up a certain number of this item in the length of time it takes our supplier to make a delivery. To estimate the number we’ll use during this time, we multiple the average daily demand by the average lead time.

How to Calculate Lead Time Demand

How to Calculate Reorder Point

Adding our safety stock level to the lead-time demand gives us our reorder point.

But what does the reorder point tell us to do? This value says that when our inventory level reaches 350, it’s time to place another order for this item with our supplier. The 350 units we have at the time we place our order are the number of units we’ll use while we wait for another delivery plus some buffer to deal with unpredictable variation.

I’ll now show you a second approach that I’ve used in situations where calculating averages and maximums of real delivery times and real daily usages is overly time-consuming, meaning that some of the dates we need for lead times is on paper or impossible to extract from a computer system because it’s in a PDF image file and not a data field we can access.

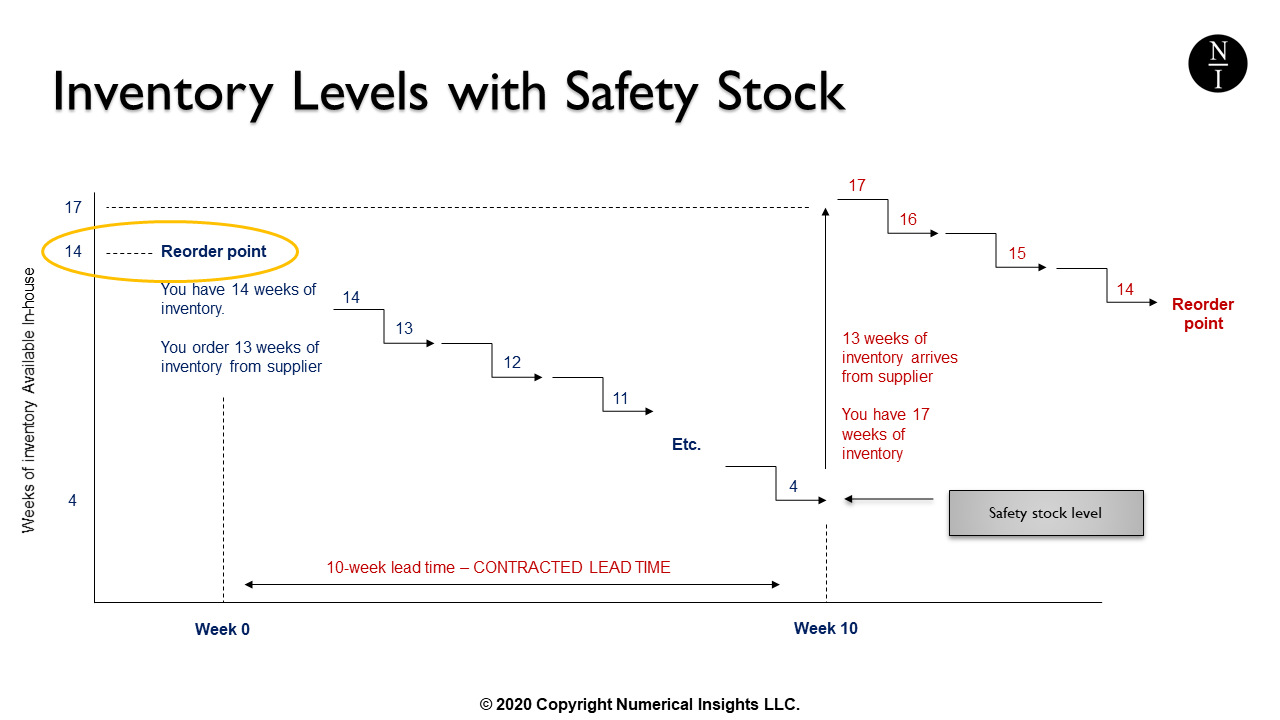

Instead of calculating a safety stock level in units, we think of our inventory buffer in terms of the weeks of inventory we want instead of the number of units… and, since calculating the variation in lead times isn’t possible because of how the data is stored, we’re going to use the contracted lead time.

In this example, the supplier’s contracted lead time is 10 weeks. We want a safety buffer of 4 weeks of inventory. This means that when we reach the point of having 14 weeks of inventory in-house, we place an order with the supplier. Our example company likes to order 13 weeks of inventory at a time because of certain production considerations. If the supplier delivers on-time, i.e. in 10 weeks, that means the new inventory should arrive just as we are reaching an inventory level of 4 weeks worth of stock.

When that stock arrives, our inventory level will rise from 4 weeks worth to 17 weeks worth. When our inventory levels reach 14 weeks worth (10-week lead time + 4 weeks worth of buffer), we will place another order… and the cycle continues. In this scenario, the 14 weeks of inventory level is our reorder point.

Order Quantity

Using this method, how much do you order? I have said that the company likes to order 13 weeks of inventory. This order amount works in the case where you haven’t had to use any of your 4-week buffer to deal with sources of variation. However, suppose this company finds that it had to use 3 weeks of its 4-week buffer to deal with a surprise order. Then the amount that they should order from their supplier next is the 13 weeks of inventory they normally order PLUS another 3 weeks of inventory to replenish their buffer back to the 4 week level.

Note: You can order any quantity you wish. That quantity determines how quickly or slowly you will reach your reorder point again.

Summary

Reorder points and safety stock levels are useful calculations to better manage your inventory, but sometimes access to the right data may force you to use an approximation for some of the values. Most companies can easily obtain daily or weekly sales data. It’s the variation in the supplier delivery times that is more difficult to obtain. While you may choose to use an approximation of the lead times by using the supplier’s contracted lead time, I do recommend studying your lead time variation at least once a year. These times tend to vary quite a bit as different industries see increases and decreases in demand. For more information on studying supplier delivery times, watch Episode 3 in this video series called How to Calculate Supplier Delivery Performance.

If you enjoyed this article or the video, feel free to subscribe to our YouTube channel to explore the other videos in this series.

About Tracey Smith

Tracey Smith is the President of Numerical Insights LLC, a boutique analytics firm that helps businesses derive value from data and improve their bottom line. If you would like to learn more about how Numerical Insights LLC, please visit www.numericalinsights.com or contact Tracey Smith through LinkedIn. To read future posts, you can join Ms. Smith’s network by signing up here.